BACON, EISENSTEIN, & TONKS

Similar concepts have different effects depending on their expressive purpose. Francis Bacon mentions the woman in the famous Odessa Steps sequence in Eisenstein’s film “Battleship Potempkin” as having influenced his portraits. Judging by appearances, he was more influenced by the war work of Henry Tonks. But you’d never mistake a Tonks for a Bacon.

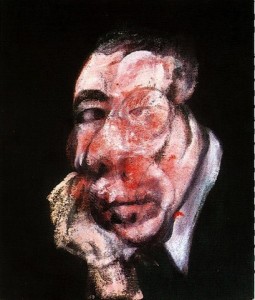

Bacon – Head III 1961 (artquotes.net)

Tonks (1862 – 1937) was a doctor as well as a painter. A war artist in WWI, he combined his skills to do pastels recording facial injuries. They are striking both for their clinical frankness and personal observation. These afflictions are borne by breathing individuals. So it’s surprising that they are not more moving. Tonks doesn’t achieve more than a tepid emotional engagement.

In part, no doubt, this is because his aim was reportorial rather than expressive, but it’s also because his attitude is very pale. These are little portrait studies, with humdrum bits of background and highlights in the hair getting the same attention as the wounds. His sitters look bored with sitting. No doubt they were. So, it seems, was he.

His “real” work was genre stuff (right: “The Pearl Necklace” 1905). It’s hard to believe that the same person could have done “the Pearl Necklace” and the battle wounds, but the genre sensibility–scenes that charm because they are familiar and comfortable–oddly pervades both aspects of his work. He describes the girl’s dreamy state, however trite (her nightgown is slipping off, but so chastely that you hardly notice); he describes Frederick Cholmondeley, however horrific; he isn’t passionate about either of them.

Eisenstein’s woman is less gory than a Tonks, but carries more punch because Eisenstein’s purpose was to excite horror, not convey information. Bacon is able to be so strong–when he isstrong, as in Head III above–because his images have no responsibilities beyond his own head. He can follow them or push them wherever they happen to go.

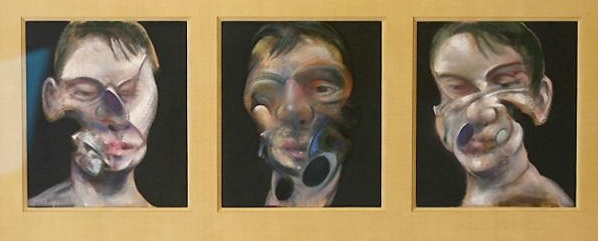

But his work can also get piddly, as in the 3 Studies of a self portrait. These are just playing with the dissolution of forms. They look as if Bacon had smeared his mirror with vaseline and copied the result. They are modernist genre stuff–no more moving than the Tonks pieces, and of far less social utility.

reprise of 11/4/11