As an art student in the ’20s, the late Erle Loran lived in Cezanne’s studio, and went about the countryside taking photos of the motifs Cezanne had painted years before. Later he wrote Cezanne’s Composition: Analysis of his form with diagrams and photographs of his motifs.* It’s a difficult and tedious book; I recommend it highly. It offers real insights into how a great artist transformed what was in front of him into art, with the caveat that it is more in the nature of a resource than an authority. In the face of his subjects Cezanne was the boss, and to my eye, Loran doesn’t always catch his train of thought. But these are quibbles. Loran secured information nobody else did, and now we can toy with it at our leisure.

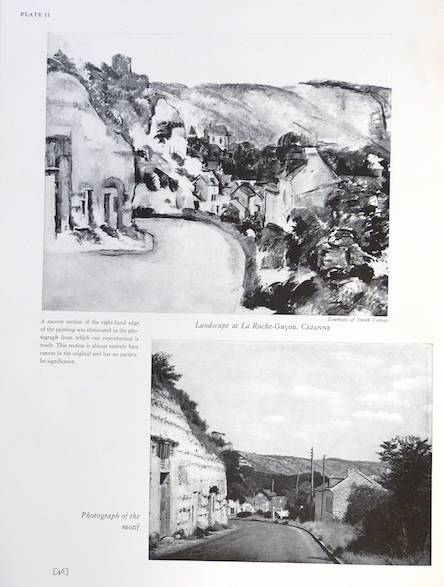

The meat of the book consists of pages like the one to the right, where Loran matches a painting with his snapshot of what Cezanne was looking at. More or less. In this case, Loran was standing in the middle of the road, while Cezanne, as you can see from the painting, set up his easel on the margin, and more directly opposite the building to the left. We can see that both by the flat-on angle of the building, and because if we go a few steps down the road a good deal of the village and the castle on the hill, almost hidden in the photo, come into view. Loran seems to have taken his snap from the spot where things looked most like the painting, but Cezanne probably worked in two or three different places where he could see whatever bits served whatever part of the composition he was after at the moment.

!["Landscape at La Roche-Guyon" 1900-1906 [ibiblio.org]](http://www.stanwashburn.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Cezanne-Roche-Guyon-1900-06-ibiblio.org_.jpg)

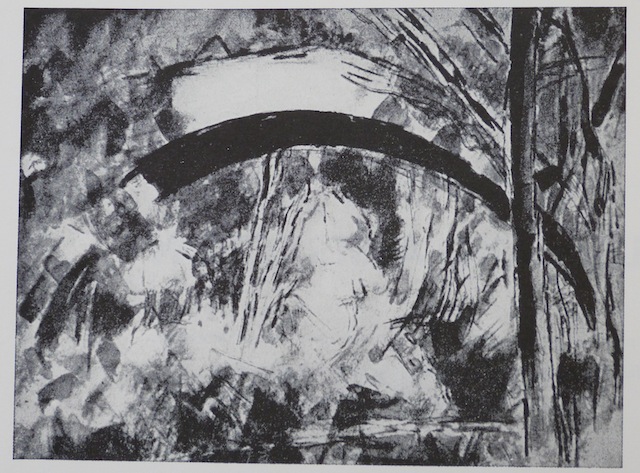

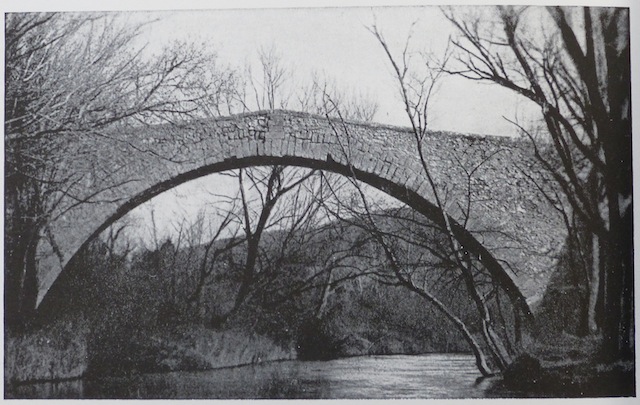

Time had overtaken many of Cezanne’s motifs before Loran photographed them. Trees grew, bushes disappeared, buildings came and went. Even so there are several fascinating cases in which essential forms and perspectives are present, and you can see how the artist pushed and pulled to get what he wanted. In the example below, a watercolor, he has dissolved the sturdy subject into a salad of brushstrokes, one here, one there, until stone and trees, dark and light and air all share a common solidity.

Cezanne’s Composition Erle Loran University of California Press — written in 1943, updated many times, still available.

The b&w images in this post are lifted from the book.