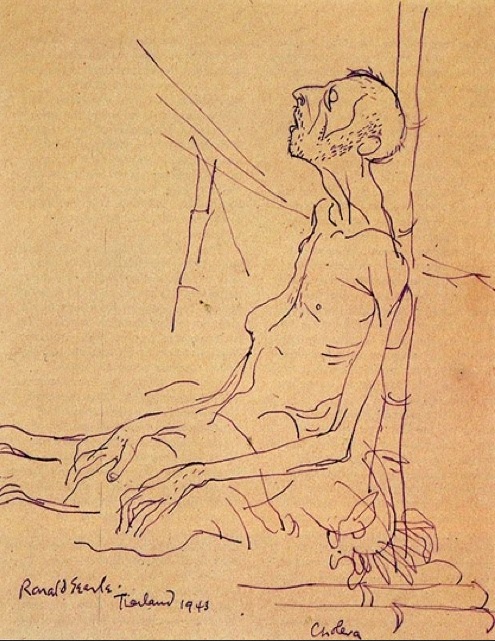

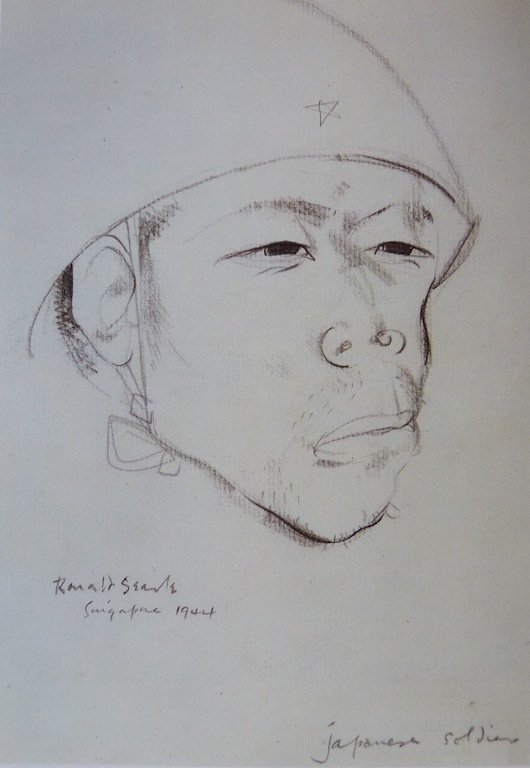

Ronald Searle (1920 – 2011), famous for his St. Trinian’s girls and New Yorker cover cats, was a young enlistee in the Royal Engineers who had just arrived in Singapore when it fell to the

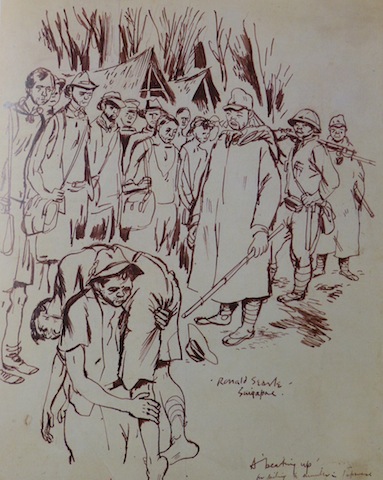

Japanese in 1942. He would be a prisoner until the end of the war in 1945. During that time he made hundreds of drawings which he hid in the beds of the cholera patients since the camp guards wouldn’t go near them. He was just out of art school; his drawings are not stylish, but their power, arising from a combination of attitude and directness, is unsurpassed.

He did them as evidence of how the POWs were treated, not thinking he would survive.

It’s true, of course, that the intimate nature of such small-scale works can’t touch the big picture. The drawings are small, and war is huge. But when the picture is big enough, the small scale–where war happens–gets lost.

![[Wikipedia]](http://www.stanwashburn.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Picasso-Guernica-1937-Wikipedia.jpg)

It seems we have to choose. Goya’s “Disasters of War” etchings, like Searle’s drawings, are close-ups of this or that appalling moment. Picasso’s “Guernica” is the famously grand, symbolic representation of war, but its labored imagery, enthralled as it is to decorative effectiveness, doesn’t hold a candle to Goya or to Searle if the point is understanding of the subject. Some art is meant to be self-referential and life-enhancing, while some is meant to be instructive. Both purposes are worthy, but when, as in the case of “Guernica,” they get muddled, our thinking gets muddled as well. As his drawings show, the young Ronald Searle knew exactly what he thought.

Illustrations from Searle’s 1986 book To the Kwai – and Back War Drawings 1939-1945