ARTHUR DEVIS

The portraits of Arthur Devis (1712 – 1787) can seem quaint when compared with grander portrait styles, but they are less convention-bound, and have their own curious vision. The spaces are large and dim, and get paler as you look into the farther rooms. The views visible through the windows are just like the landscapes on the walls. The people seem almost lost in their great, sparely furnished houses. They are decked out in their finest, clearly posing, but seem distracted, as if thinking about something else.

The figures are planted very firmly in the middle of their spaces, but the spaces are odd: Sir Roger, to the right, seems to live in a funhouse where floor and ceiling almost meet at the back wall. His monstrous desk slides into the picture from the wings. His feet are planted square across the picture plane as if to say, “the eye stops here,” and also, it seems, to arrest the progress of his desk. His pose, however, is active, and the front of the desk and his chair shift the eye back into space, and link it to the background. A more conventional painter would have flattened the floor and elevated the ceiling. But if you look at Sir Roger’s space as composed of abstract shapes, almost flat above and below, with a busy clutter of warm reds and the strong blacks and whites of the figure across the middle, it’s very satisfying.

The Bulls are composed similarly. The rug is parallel to the bottom of the space, like Sir Roger’s feet, but Mrs. Bull is set on the oblique, like the desk, with her hemline leading to Mr. Bull’s legs, which continue it up to his face so that he doesn’t get lost even though he’s smaller and dimmer. Here, too, the strongest darks and lights are reserved for the figures so that they always recall the eye when it wanders into the large space around them.

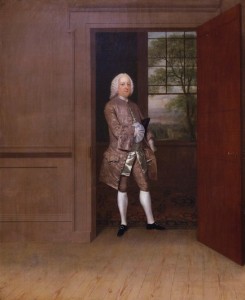

Then we have this odd pose in a doorway. The farther room is carpeted, in contrast to the considerable expanse of bare floor in the foreground; the view through the window is lush and complex as opposed to the unadorned paneling and door closest to us. Spare and light out here, dark and rich beyond. Some inner sanctum? If so, and if that is important to the gentleman, why not set the portrait in that room? Perhaps because Devis liked this composition. And the darkness beyond sets off the figure very effectively, just as the fireplace sets off Mrs. Bull.

As designs, these three portraits are striking and ingenious; as social advertising or self-congratulation, which is usually the point of portraiture, they are perhaps dubious. This may be why Devis fell out of fashion, and Sir Joshua Reynolds, among others, full of flash and dash, became the rage. It seems too bad. The Reynolds below is perfectly well painted, but it’s obvious, snobby, and sentimental all at once.

Certainly, Devis’s vision was very personal to himself, and perhaps Lady Elizabeth and her peers, shopping around, wanted less presence of the painter, and more attention to their own good looks and fine clothes and stylish hair. And children, of course. As Gertrude demanded of Polonius, “More matter with less art.”

Sir Joshua bores me, but I always come back to Devis with fascination.

This post is a reprise of October 22, 2011