THOSE ENGLISH!

I think of English art before the mid-19th Century or so as a decorous celebration of life of or from the viewpoint of the upper crust. When Constable’s Bishop (down in the lower left-hand corner–click to enlarge) looked around him and saw harvest wagons, I expect he saw something idyllic like the Gainsborough. Perhaps I sell him short, but that’s the impression I get.

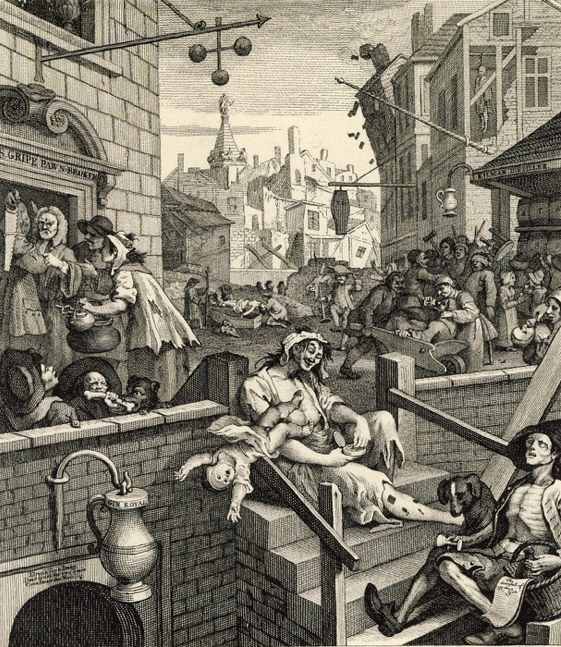

Well, there was Hogarth. No doubt the Bishop got to London from time to time, where Gin Lane would have been hard to overlook. But Beer Street, with its well-fed, contented workers, is the urban counterpart of Gainsborough’s wholesome countryside.

But then we come to George Stubbs (1724-1806), and this painting of dragoons. The class order is clear enough, but that is not the point. This is not a social document. It is a self-referential work of art. The overwhelming impact is one of operatic unreality.

Most posed paintings make at least a pretense of representing a real moment, but this does not. It goes for intensity. The severe whites against the deep and unnatural blacks (how can the whites be so white when the shadows are so consuming?); the dark, romantic sky; the gorgeously abstract formation of mounted officer and three distinctly uniformed troops standing to attention. Uniformed, but not uniform: examine the two on the right, detail by detail–everything from plume to crossbelts to shoes is subtly different from one to the other.

The figures are stitched by the interlocking, greenish wedges receeding from foreground to background. And notice how adroitly the repetition of the buff color of saddlecloth and bugler’s waistcoat carry the eye across that complicated negative space between the bugler and the horse. And the odd angle of the bugle–it’s at 90 degrees to the officer’s carbine, which again bridges the gap, and subtly links them. And curves: the same curve occurs in the sabre, the horse’s neck, belly, and hind legs, the bugler’s left arm, the center trooper’s right leg.

And the horse: horses were Stubb’s speciality, which perhaps explains his attention to the elegance of the beast rather than the usual dramatic function of horses in military depictions, which is to display the intrepidity of the rider.

All together, a very unexpected, very painterly piece. Strange and wonderful. And quite a jump from Gainsborough.

(this post is a reprise of Jan 28, 2012)