Titian’s Odd Edges

I don’t quibble lightly with the great Titian, but I’m puzzled by his propensity for jamming the focus of a piece way over to the side. In his fabulous “Bacchus and Ariadne,” a great torrent of life tumbles out of the right side toward Ariadne on the left—and almost pushes her out of the painting. It’s as if a fifth of the canvas has been chopped off the left side. I picture sea and sky continuing on past Ariadne. The foreground would angle down to the lower left-hand corner so that the whole left side would be variations in blue except for those delicate stripes of warm cloud shapes and her flesh tones and red ribbon. The image would be both wilder and more mythical if it were more spacious.

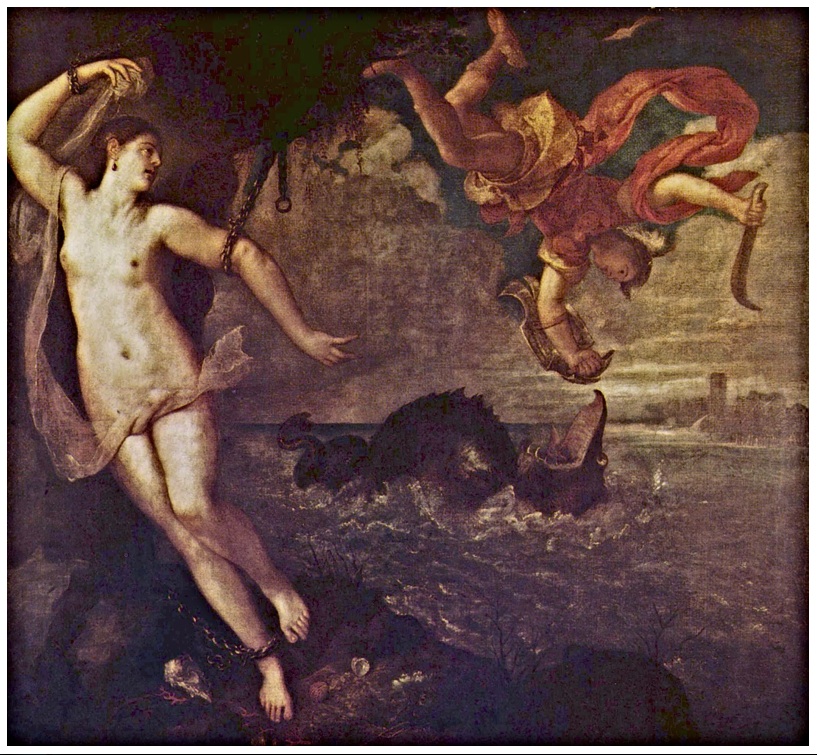

And it’s not that piece alone. In his “Perseus and Andromeda” he does the same edge-crowding thing, but here it’s even worse. Ariadne is at least held firmly in the design by various subtle devices (for example, pick any limb of hers, and you’ll find a parallel or perpendicular in Bacchus), and the terrific eye contact between the parties. But despite her chains, poor Andromeda seems to be floating away from the action. There is almost no connection between her and the battle of Perseus and the monster. But picture an additional body’s width of rock on the left to hold her in and impart more weight, more balance.

Which is how Delacroix handles it in his homage to, and rework of, the Titian. Although it must be admitted that, while avoiding Titian’s error, he falls into one of his own: his Andromeda is so sparkly white, and so self-contained, that the eye can scarcely get past her. If he’d inclined her body toward the upper right corner, the whole would have been comprehensible at a glance, and the details absorbed one by one.

Back to Titian: he does it again in his amazing “Rape of Europa,” cramping the poor bull, and driving him almost off the canvas.

No doubt he had his reasons, but I can’t think what they might have been.

On a side note, pallid reproductions of “Bacchus and Ariadne” were standard in the art history texts I had when I was in art school. I thought it a cluttered and silly piece until my first visit to the National Gallery in London. The real thing is simply stunning. The reproduction here is better than most, but still not a patch on the original. Trot along to London, and see for yourself.

this post is a reprise of April 7, 2012