Derain’s experiments

Last week we looked at the clues in Claude Monet’s early work that show how he crafted the visual information in front of him into strong art. In a similar quest, here we look at two pieces by Andre Derain (1880-1954).

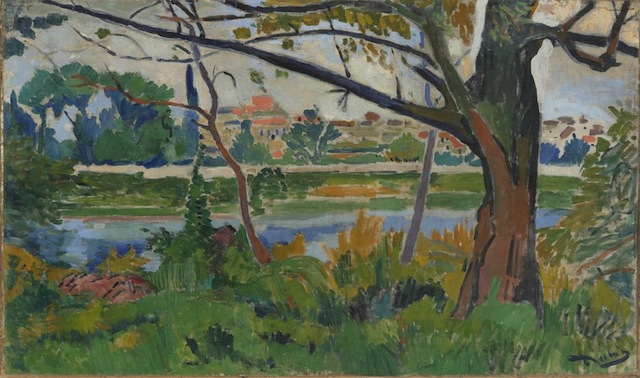

The first, The Seine at Chatou, seems to have been painted in one session with a few touchups afterwards. It seems to have been painted in the field, judging from the immediacy of the handling and a wide streak of scratchings on the left side (not visible here), as if it was dragged past a bush on the way home. It exudes a sense of exploration: he wouldn’t have painted this view if it hadn’t appealed to him, so things like that long, long branch to the left, and the awkwardly u-shaped ones on the right, are here because they were in front of him and engaged him. But there is also the compositional order imposed by a painter with formal training: the foreground tumbles in lively fashion toward the river, and the vertical bushes and trunks carry the eye up to the many horizontal stripes and shapes across the middle, locking the delightful vagaries of the scene into a coherent composition.

Now to Bridge Over the Riou, painted in the same year. This is how painters get into trouble: pushing too hard with no workable sense of a new logic, a new system. The basic compositions of these two pieces are similar: a sweeping foreground leading to a river with trees and fields beyond, stitched together by foreground trees. But now Derain goes out of his way to rebel against convention. He muddles the foreground and stifles the river. Left and right bear no relation to each other. All that clunky blue-and-green foliage stops the eye dead in its tracks. There are lots of interesting bits, but they don’t play off each other, or build a convincing new whole. The result is muddle, not an assertion of a new vision.

Or at least, not so far.